Merce Cunningham Dance Company

Brooklyn Academy of Music

Howard Gilman Opera House

October 14, 16-18, 2003

By Nancy Dalva

Copyright ©2003 by Nancy Dalva

Rolling the dice gives a moment of wonder, the imagination conjuring. A split-second later, the dice at rest, the mind becomes active.— Merce Cunningham

Of all of the multiple innovations in the work of Merce Cunningham, the use of chance is the most confusing. Such a clear thing, this toss of a die, or a handful of pennies, and yet chance is the Holy Ghost of Dance—the part of the Cunningham Trinity taken on faith, and dimly apprehended. The independence of dance as an art form–the notion that dance does not need music, but may simply coexist with it—still may seem heresy to some, but as an idea it is well understood. The separation of dance from story is now old hat, or old enough, though still giving rise to the notion that Cunningham's dances are "abstract," when dance, because it is done by people, can never really be abstract. But chance! Chance makes people think of randomness, of disorder, of improvisation, of fate and fortune, of things made up as they are happening, or just before. Nothing, though, could be further from the Merceian truth, which is quite the opposite. His is not the unhinged Miltonic world of Paradise Lost, where "Chaos umpire sits," and "Chance governs all." Not in the slightest. In his world, Merce governs all, even when by a kind of non-doing, this latter being neither benign nor malign, but a kind of sovereign absenting of ego. Even when Cunningham does not make choices—as when, for instance, he leaves the decor to the art director, or some similar personage, who chooses the artists; and likewise hands off the music—he has chosen the chooser. The truth is that in his world, Cunningham is God. Every choice, or non-choice, is made by him.

Of all of the multiple innovations in the work of Merce Cunningham, the use of chance is the most confusing. Such a clear thing, this toss of a die, or a handful of pennies, and yet chance is the Holy Ghost of Dance—the part of the Cunningham Trinity taken on faith, and dimly apprehended. The independence of dance as an art form–the notion that dance does not need music, but may simply coexist with it—still may seem heresy to some, but as an idea it is well understood. The separation of dance from story is now old hat, or old enough, though still giving rise to the notion that Cunningham's dances are "abstract," when dance, because it is done by people, can never really be abstract. But chance! Chance makes people think of randomness, of disorder, of improvisation, of fate and fortune, of things made up as they are happening, or just before. Nothing, though, could be further from the Merceian truth, which is quite the opposite. His is not the unhinged Miltonic world of Paradise Lost, where "Chaos umpire sits," and "Chance governs all." Not in the slightest. In his world, Merce governs all, even when by a kind of non-doing, this latter being neither benign nor malign, but a kind of sovereign absenting of ego. Even when Cunningham does not make choices—as when, for instance, he leaves the decor to the art director, or some similar personage, who chooses the artists; and likewise hands off the music—he has chosen the chooser. The truth is that in his world, Cunningham is God. Every choice, or non-choice, is made by him.In the chance procedures Cunningham uses at some point in the making of each of his dances, all the available elements are his. This movement first, or that one? The moves are all his. What number of dancers? The number available is up to him. Chance is simply a marvelous surprise-generator. And Cunningham likes surprises. Thus he must have enjoyed his season this past week at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where chance procedures went public.

Opening Night

Iacta alea est.

The die is cast.

(Julius Caesar, 1st Century B.C.)

The world premiere of Split Sides, already infamous for the commissioning of two rock bands, the British Radiohead (post-modern rockers with an enormous following of teenage and twenty-something literati), playing live opening night, and the Icelandic Sigur Rós, who sweetly fall in love with the dancers and, as it turns out, will stay on in the pit for the whole run. Each band has composed a piece of twenty minutes and Cunningham has made two dances of twenty minutes (known as A and B ).

The company's general manager, Trevor Carlson, whose energizing notion it was to commission the rockers, has also arranged for two sets, both by photographers. One is by the 18-year old Robert C. Heishman, who works in black and white ( often using cameras made from everyday objects, with film in one end and a pin hole at the other.) The other is by Catherine Yass, working in color (using a large-format camera, and layering and lighting techniques to produce composite images with manipulated and heightened coloration).

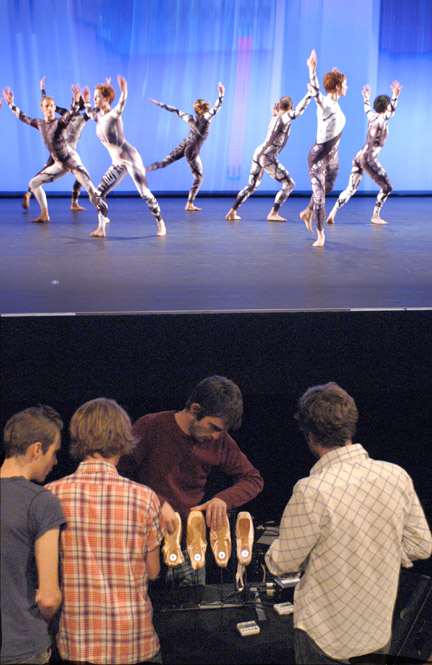

The company's general manager, Trevor Carlson, whose energizing notion it was to commission the rockers, has also arranged for two sets, both by photographers. One is by the 18-year old Robert C. Heishman, who works in black and white ( often using cameras made from everyday objects, with film in one end and a pin hole at the other.) The other is by Catherine Yass, working in color (using a large-format camera, and layering and lighting techniques to produce composite images with manipulated and heightened coloration).James Hall, the resident costume designer, has in his turn made two sets of costumes, one black and white unitards, the other silky-looking bell-bottomed jumpsuits, all sleeveless, with acid-trip coloration. Each set of clothes is similarly imprinted with a network of black crisscrosses and branches suggesting twigs, or spider webs. So that we can see the whole thing, James. F. Ingalls has been called upon to devise interchangeable light plots, which, as a convenience, are given numeric names. One is from the 200 Series; the other from the 300 Series.

Shortly before each performance—so as to allow for a period of rehearsal-- Cunningham hands someone a die to cast, to determine the order of the two dance parts. The other elements are selected on stage before each performance of Split Sides.

On opening night, the curtain went up on Michael Bloomberg, the Mayor of New York City, who introduced Merce Cunningham and two of his former artistic directors, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, there to roll the die. Three titans of twentieth century modernism, gamely chancing it in the twenty-first. Cunningham walks with a cane now, and not easily, and the Merlinishness he has long exhibited is in full flower. He really does seem to travel backwards through time, meeting up with the young and showing them where the future lies. Rauschenberg has suffered a stroke, but his merriness seems intact. He is, as ever, a loveable public personage, while Johns has achieved a truly forbidding and magisterial aloofness, not the usual aspect of someone who is about to roll snake eyes (or not). Joining them on stage were the company's patroness saint, Sage Cowles; the bands; and the designers; and the dancers, who popped up now and then as they jumped to maintain a warmed-up state.

After Cunningham explained the chance process, to no small confusion and amusement on the part of the listeners, a die was produced for an on-the-spot determination of which of each two-part production component would go first. (This was sorted out by declaring one half of each odd, the other even.) Each die roll was projected on a screen, with the following results (including the pre-performance dance toss): even, even, even, odd. This yielded the following two-part version of the work:

Dance: A/B

Music: Radiohead/Sigur Rós

Sets: Heishman/Yass

Costumes: black&white/color

Light: 300/200.

"A gimmick," a man behind me would mutter later in the week, on the last night. (And it does take a lot of explaining, before one can even begin to get at the dancing itself.) But as it turned out, not a gimmick, but a revelation.

For while the elements stayed the same from performance to performance (although I guess you could quibble about the music, which has some built-in allowance for spontaneity), they would vary in their combination, though very slightly, as chance had it. The affect of the choreography, and the effect, would change from performance to performance, depending on the order of its arrival, what it wore, and where it was. (Just as you yourself appear different in a bathing suit at the beach or a winter coat at a funeral, though you may be standing the same way, and thinking the same thing.) One could make an aesthetic judgement about the various results; one might have a preference. From evening to evening, one went home floating on air, or shuddering. The audience response was vivid each night—the houses were sold out, right up to the rafters—but the group preference was clearly for color, for pleasure, and for a happy ending. So it was on the first night, which went from dark to light.

For while the elements stayed the same from performance to performance (although I guess you could quibble about the music, which has some built-in allowance for spontaneity), they would vary in their combination, though very slightly, as chance had it. The affect of the choreography, and the effect, would change from performance to performance, depending on the order of its arrival, what it wore, and where it was. (Just as you yourself appear different in a bathing suit at the beach or a winter coat at a funeral, though you may be standing the same way, and thinking the same thing.) One could make an aesthetic judgement about the various results; one might have a preference. From evening to evening, one went home floating on air, or shuddering. The audience response was vivid each night—the houses were sold out, right up to the rafters—but the group preference was clearly for color, for pleasure, and for a happy ending. So it was on the first night, which went from dark to light.The first Split Sides began with black and white costumed dancers in front of a black and white backdrop depicting what was perhaps a ruined roller coaster, glimpsed through fog. The lighting throughout enhanced directionality—if the dancers looked up, light took their upturned faces. From the sides, light enhanced curves, sharpened angles. There were unobtrusive shifts in lighting levels, giving a sense of time passing, and of narrative—light suggesting, as it does, time of day, and time passing, or place changing, without overtly imposing meaning. Radiohead offered a sonorous and serious score, varied in texture, and with no overwhelming beat. It was not so very different in kind from other electronic music the company has commissioned in the past, and one felt the rockers were making a bid to follow in the serious footsteps of the electronic composers who have preceded them on the company roster. At any rate, they gave themselves over to the cause at hand, and served the Cunningham well. (To those strict Cage/Cunningham traditionalists who expressed abhorrence at the notion of the music having a beat, I would point out, just in passing, the scores by David Tudor for Sounddance and Michael Pugliese for August Pace. To those who were concerned by the potential intrusiveness of lyrics, which were at any rate few, I would mention Robert Ashley's wildly overbearing score for Eleven. Not that there's anything wrong with complaining, if one must; but it would be wrong to complain that what was happening was newly vexing.)

If the whole of this first half of Split Sides was wintry, hermetic, arctic, with the observing mind bouncing off the whole thing to careen around feeling very much alone, and the feeling heart pierced to the core, the second half was, to borrow an expression from Cunningham, an "all candy dinner." The effect was of starting off in Kansas, and ending up in Oz.

The costumes were happy and bright and sugary, the photographic backdrop smeared buildings into towering pastel after dinner mints, and Sigur Rós reached for a xylophone, a battery of timpani constructed of toe shoes, the recorded sounds of a baby cooing, and some wind-up devices they happily used to tick-tock along with what they could see from the pit. Thus as Derry Swan spun thrice around her partner Cedric Andrieux, Venus cavorting with Mars, the musicians made merry matching sounds. (For those who were appalled by this, I would only point out that the late David Tudor, Cunningham's music director after Cage's death, and a long time pit musician and composer for the company, by his own admission did the same thing, though not in such a rudimentary way. He admitted this backstage at the Paris Opera, after the first performance of Enter, when he could be seen ramping up the sound when the stage grew dark and dull and overshadowed by the set, as if in counter-balance. In other words, if there are rules, they've already been broken, albeit broken better.)

The costumes were happy and bright and sugary, the photographic backdrop smeared buildings into towering pastel after dinner mints, and Sigur Rós reached for a xylophone, a battery of timpani constructed of toe shoes, the recorded sounds of a baby cooing, and some wind-up devices they happily used to tick-tock along with what they could see from the pit. Thus as Derry Swan spun thrice around her partner Cedric Andrieux, Venus cavorting with Mars, the musicians made merry matching sounds. (For those who were appalled by this, I would only point out that the late David Tudor, Cunningham's music director after Cage's death, and a long time pit musician and composer for the company, by his own admission did the same thing, though not in such a rudimentary way. He admitted this backstage at the Paris Opera, after the first performance of Enter, when he could be seen ramping up the sound when the stage grew dark and dull and overshadowed by the set, as if in counter-balance. In other words, if there are rules, they've already been broken, albeit broken better.) This part of the work also contains two passages of enormous warmth—a solo danced by the beautiful Jonah Bokaer, and a quadruple duet—that is, the same duet multiplied by four, that reads like a sermon on love, with each couple doing the same thing, but in its own touching and individual way. The Bokaer solo has some signature Merceian animal gestures—a swanny head preening on a feathery wing, a shaking of water off the face—but placed within a context of sculptural poses straight out of Donatello. Bokaer has mastered the Cunningham way of being one place and the next with no visible means of transit. He's mastered the invisible jump. It may embarrass him to hear it, but Bokaer has a radiance bespeaking goodness, and belief. (Not for nothing did John Cage and Cunningham name an early work Credo in Us.)

Bokaer appeared again in the quadruple duet, which incorporate a ravishing figure in which the woman climbs onto her partners' back as he lunges to one side, is carried over onto his front as he shifts to a lunge on other side, and knifes her legs over to end up behind him again. This is a beautiful and rapt a phrase as Cunningham has made, and for it he chose, as he usually does now, to pair Jeannie Steele (his Catherine Deneuve) with Bokaer, thus giving his senior female the dishy reward of his youngest man. (Like handing Nureyev to Fonteyn, though the age difference here is not so great.) Here too were Cheryl Thierren (Merce's still unravished bride of quietness, who has spent so much of her career in relevé, with one arm raised, the essence of the feminine, of water, of respite and of calm) paired with the classical exemplar Ashley Chen, both incredibly reticent, but with the uncanny ability to convey the feeling of flesh on flesh, as when he places his hand on her armpit, a move of really shocking intimacy that is then repeated by the other couples—the Olympian Swan and Andrieux; and Lisa Boudreau (a great beauty of harmonious proportions ) dancing with Daniel Roberts (a great brain whose dancing is powered by thinking).

Despite these lush interludes, and also a comedic trio reminscent of the Cunningham videodance Delicomedia, much of Split Sides is—like the program opener Fluid Canvas, a work new last year and new to New York on this season—fiendishly difficult, and notably spare. Both dances can readily be characterized as Late Cunningham, with the choreographer frequently working in multiple images of the same figure—for instance, eight dancers each doing the same thing, but each with a different front, so we see the step from different sides at the same time. 360 degrees, all from your seat. Cunningham always stands at a kind of choreographic South Pole where every direction is North; or alternatively a North Pole, where every direction is South. For him, every direction is front. Here he fractures the figure into multiples, in angular, sparse poses that refract each other, so that the stage is a prism. This part of his work is unforgiving, and from a distance, chilly. Up close, as from the second row, the personalities of the dancers enliven it. Where you sit makes the dance different as much as any chance changes rung before the curtain—but that is always true at a dance performance. You can sit back, and see the night sky, or sit close, and see the human condition.

Despite these lush interludes, and also a comedic trio reminscent of the Cunningham videodance Delicomedia, much of Split Sides is—like the program opener Fluid Canvas, a work new last year and new to New York on this season—fiendishly difficult, and notably spare. Both dances can readily be characterized as Late Cunningham, with the choreographer frequently working in multiple images of the same figure—for instance, eight dancers each doing the same thing, but each with a different front, so we see the step from different sides at the same time. 360 degrees, all from your seat. Cunningham always stands at a kind of choreographic South Pole where every direction is North; or alternatively a North Pole, where every direction is South. For him, every direction is front. Here he fractures the figure into multiples, in angular, sparse poses that refract each other, so that the stage is a prism. This part of his work is unforgiving, and from a distance, chilly. Up close, as from the second row, the personalities of the dancers enliven it. Where you sit makes the dance different as much as any chance changes rung before the curtain—but that is always true at a dance performance. You can sit back, and see the night sky, or sit close, and see the human condition. Second Night

Times go by turns, and chances change by course,

From foul to fair, from better hap to worse.

Robert Southwell (Times go by Turns, 1595)

The throws of the die yield even, even, odd, odd. Only one element changes, the costumes. Thus:

Dance: A/B

Music: Radiohead/Sigur Rós

Sets: Heishman/Yass

Costumes: color/black&white

Light: 300/200.

Rather surprisingly, the flipping of costumes makes a new dance—or perhaps the same dance with a different mood. In fact, Split Sides looks very moody indeed this way, resembling some sort of cruel psych experiment. To wit: in an arctic landscape, some Tahitians are set down. And vice-versa in the second part. Instead of harmony, disjunction; and the drama of contrast, but only visual. (These would not be the inherent contrasts of Cunningham choreography, where fast—and these days faster, faster, faster!—is set against slow, light against heavy, aerial against grounded, and so forth.) In sum: the dance was easier on the eye last night, and it has given up its unity of impression. This isn't to say there is a better version or a worse. But there is a pleasant and a much less pleasant. The disharmony tonight only points up the exigencies of this particular format, with the parts transposable.

By neccessity, Split Sides looks like a Cunningham Event, one of those signature amalgams of parts of various dances, rather than one of the great repertory works possessed of an ineluctible inevitablity. Because the halves can run in either order, they have to have beginnings and ends that won't put a dancer in two places at once, or in one place wearing one costume one second, and another the next. Thus the troupe is divided in half at signal junctures. But company and continuity are not the only things split.The body itself is split every which way—one half against another, side to side, top to bottom—and dancers themselves are split, even when dancing together. As evidence there exists the most difficult, cool, clinical duet ever devised by Cunningham, danced by two virtuosi of the impossible, the firebrand Holly Farmer and the soulful Daniel Squire. In this encounter, neither seems to have anything to do with the other, and yet they intersect, with hostile inadvertence. Finally, in anything but abandonment—she gives the feeling she could just reverse course with no need of a partner—Farmer falls back into Squire's arms in just the way that Cathy Kerr fell back into Alan Good's arms in the Cunningham masterpiece Points in Space. So similar, so different.

By neccessity, Split Sides looks like a Cunningham Event, one of those signature amalgams of parts of various dances, rather than one of the great repertory works possessed of an ineluctible inevitablity. Because the halves can run in either order, they have to have beginnings and ends that won't put a dancer in two places at once, or in one place wearing one costume one second, and another the next. Thus the troupe is divided in half at signal junctures. But company and continuity are not the only things split.The body itself is split every which way—one half against another, side to side, top to bottom—and dancers themselves are split, even when dancing together. As evidence there exists the most difficult, cool, clinical duet ever devised by Cunningham, danced by two virtuosi of the impossible, the firebrand Holly Farmer and the soulful Daniel Squire. In this encounter, neither seems to have anything to do with the other, and yet they intersect, with hostile inadvertence. Finally, in anything but abandonment—she gives the feeling she could just reverse course with no need of a partner—Farmer falls back into Squire's arms in just the way that Cathy Kerr fell back into Alan Good's arms in the Cunningham masterpiece Points in Space. So similar, so different.Third Night

All nature is but art, unknown to thee;

All chance, direction which thou canst not see....

(Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man, 1733)

Everything turns up even. Thus:

Dance: A/B

Music: Radiohead/Sigur Rós

Sets: Heishman/Yass

Costumes: black&white/color

Light: 200/300

This is the same as the first night but with the lights switched, by far the most subtle change one can ring here. Light, which enables us to see, is hard itself to hold in the mind, to compare one half to the other. At any rate, this combination has the happy result of bathing the quadruple duet in a golden glow.

Closing Night

Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard.

A throw of the dice will never eliminate chance.

(Stéphane Mallarmé, 1897)

By now there is consternation in the front of the house, and a certain disbelief backstage. Night after night, and still the same order of music, dance, set! (If anyone thought the results were rigged, this certainly proved contrary—one somehow expected, and even hoped for a dog's dinner night to night, with everything all mixed up.) The pre-show cast inverted the dance order, so hopes were high at the public tosses—but the die came up odd all the way.

Odd! Odd! Odd! Odd! The two halves of the production were identical to the night before, but flipped. Thus:

Dance: B/A

Music: Sigur Rós/Radiohead

Sets: Yass/Heishman

Costumes: color/black&white

Light:300/200

Same old, same old, one should think. But no. The consequent change to the work is astonishing. Brought forth by a few rolls of a single die, tragedy comes calling. The first part, all warmth and sweetness, with young Jonah in his solo and the four couples in their love song, yields to the harsh wintry second part, with the dancers looking like extremely intelligent aliens who have just this moment come to inhabit human bodies, trying them out for the first time without knowing any of the human rules of moving. The eye glances off what it does not recognize—the glinting surface of the unfamiliar, as glances, too, the mind. Bleak, bleak, bleak—the summer of the first half giving way to winter, sunlit youth yielding to starlit age, remote and chill.

Same old, same old, one should think. But no. The consequent change to the work is astonishing. Brought forth by a few rolls of a single die, tragedy comes calling. The first part, all warmth and sweetness, with young Jonah in his solo and the four couples in their love song, yields to the harsh wintry second part, with the dancers looking like extremely intelligent aliens who have just this moment come to inhabit human bodies, trying them out for the first time without knowing any of the human rules of moving. The eye glances off what it does not recognize—the glinting surface of the unfamiliar, as glances, too, the mind. Bleak, bleak, bleak—the summer of the first half giving way to winter, sunlit youth yielding to starlit age, remote and chill.At the curtain calls, radiant Jeannie Steele—whose love for the dancing so suits her to be the choreographer's guardian angel—stepped off to get Cunningham. He entered on her arm and joined his troupe, taking his place at the far left of the stage. The company stepped back to allow him a solo bow, then turned as one to applaud him, so courteous, so gallant, so persevering, standing there in a brilliant orange shirt. Shortly thereafter, the curtain came down on the Merce Cunningham Dance Company's New York season. The company now will fly off to other theaters, other performances, Cunningham as ever traveling along to run the show from his accustomed place just off stage. Whatever chance procedures he has used in making the repertory will have been made, the process striking sparks to his own creativity. He will not, as he never has, be taking any chances on his dancers, whom he selects. For all the freedom he allows his composers and his visual artists, they are, at the least, known quantities when they are selected, and at any rate their work is made before the curtain rises. But there is indeed a rogue element at play at the time of the performance—an element that is random, uncontrollable, unknowable ahead of the event. Dicey in every way. That element would be us, coming into the theater with our minds cluttered and our sensibilities settled, carting around the baggage of the day. Night after night, year after year, in city after city, Merce Cunningham takes a chance on us.

All photos: Jack Vartoogian.

Originally published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 1, Number 4

October 20, 2003

Copyright ©2003 by Nancy Dalva