Lincoln Center Festival

Ashton Celebration

My Friends Pictured Within

Enigma Variations

and The Two Pigeons

Birmingham Royal Ballet

Metropolitan Opera House

New York, NY, USA

July 9, 2004

W

What a wonderful ballet "Enigma Variations" is—there's really nothing more one could ask of a work of art than this. It is rich on every level, and has an unusual appeal for a ballet: Sir Frederick Ashton's sublime narrative work is about grown-ups in a grown-up world. No one is enchanted, though someone may be imaginary. No one is an animal, though someone portrays a dog while telling a story about one. No one has magic powers. Never for a second do you have to suspend your disbelief. In this "Enigma Variations" is a triumph of naturalism, but also of neo-classicism—the choreography is all ballet, though tempered with everyday human gesture, and hence humanized. We have been lucky to have the Birmingham Royal Ballet here to perform it, and to perform it in a way more satisfactory, as an immediate experience, than I remember a previous Royal Ballet performance here to have been. Although there could have been more variety in the tempi among the variations–the fast faster, the slow perhaps slower—the ballet was in every way acceptable, which is saying a very great deal. One demands the most when a beloved work is returned to one's attention, calling up everything one felt upon first seeing it, and everything one has learned to feel since. My only complaint is that I would like to see it again, and it is over.

The key to "Enigma," is the decor. Indeed, the real muse of this ballet is the designer, Julia Trevelyan Oman. She first proposed the work in the 1950s, as the Ashton historian David Vaughan tells us in "Frederick Ashton and his Ballets" (Knopf, 1977), but Ashton did not take her up on the idea until 1966. Why not? "For one thing, " Vaughan tells us, "Elgar's music did not appeal to him." From the evidence of the ballet, Ashton later fell deeply under the music's spell (or he merely did such a fantastically good piece of work that you think he did), as have any number of other people who have sought to explicate the enigma—or enigmas—of Elgar's title, which has to do with a musical theme—or themes—said to be encoded in the ballet, perhaps in counterpoint. Without going into it in any great detail, I will just say that a leading contender among code theorists for the source of embedded theme is "Rule Britannia" though there is one rump group favoring Mozart . At any rate the ballet itself is very British, though there is a certain moment at the end, when Sir Edward kneels to his wife, that recalls the end of "The Marriage of Figaro," when the Count apologizes to his countess. (Ashton is a genius of apology, as one saw particularly on this bill–and coo--also comprising "The Two Pigeons," which ends in remorse and forgiveness.)

It was Ashton's great achievement not to explain the enigma, but to create the atmosphere of enigma though characterization, directly derived from the sound-portraits of his intimates that make up Elgar's theme and variations, to whom he referred as "my friends pictured within." The Ashton enigma is this: we are not sure of the exact nature of Elgar's relationship to the women in the ballet who are not his wife, and indeed—in the case of a muse figure who bourées in from the garden cloaked in mist—whether one woman is conjured by his imagination. She is outside the house—the domain of Lady Elgar—but inside. She is inside Elgar's head. His relationship with his publisher Jaegar is also subject to interpretation, though to intuit anything romantic would be more Freudian than the ballet itself. Indeed, if you want to go that far, there is in fact a famous trio that can be interpreted though Freudian triangulation as Elgar experiencing his wife, who was some eight years his senior, as his mother, and his publisher as his father.

Interior, exterior. The set the designer eventually devised is exactly that. The frontispiece is a copse of trees though which you glimpse, on the left, a hammock, with a fully dressed table set next to it, compete with lace over-cloth. In the center, a stone arch marks the entry to the garden, with woods beyond. On the right, a spindle-bannistered flight of stairs, with an intermediate landing. Beneath the stairs, another arch, neoclassical, but hung with a patterned curtain on a rod. Before that there is a table and chairs, flanked by a wall with a fire place featuring a rather elaborate yet reticent super-mantel, inset with what appear to be enamel plaques. Copse, table, country house, fireplace, table, chairs. The entire affair could house "The Three Sisters," "The Cherry Orchard," or "Uncle Vanya"—the last of which Chekhov wrote in 1897, the year before Elgar wrote the Enigma Variations.

No wonder, then, that viewers find correspondences between the ballet and the plays. Chekhov and Elgar were contemporaries, though of course Ashton himself was looking back to the Worcestershire of the period. (See

Elgar's boyhood home, to which he kept a close attachment.) Because the women's skirts have been shortened from the correct period length—most merely to the ankle—to make dancing possible, the dresses for the ballet appear Edwardian, but Victoria was still queen when Elgar wrote his programatic score, to which the choreographer cleaves with complete fidelity. The Elgars of the ballet are eminently Victorian.

Ashton, on the other hand, was an Edwardian. Born in 1904, he remembered seeing King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra "riding in the royal" coach (Vaughan, p. 1) on a visit to London, but his was not an English boyhood. Born in Guyaquil, Ecuador, he spend his childhood in Lima, Peru, a Spanish colonial city with a coastal desert climate. In other words, Ashton was an ex-pat.

This, I think, is the ultimate basis for the dichotomy of exterior and interior in the "Enigma." Ashton framed it through the lens of time. He would have known, for instance, what great sorrow Elgar would later experience at the outbreak of World War I; a sorrow-to-come that ineluctably colors the Elgar character's duet–part of the "Nimrod" trio—with A.J. Jaegar, his German publisher. But Ashton also framed the work though the lens of the outsider. Considered the most English of choreographers, he was portraying the most English of composers, but with all the clarity, and careful selection of syntax, of the foreign-born and raised.

The "Nimrod " begins with the publisher adjusting his glasses—on July 9, at the Met, Pierpaolo Ghirotto danced the part, looking much like the originator, Desmond Doyle, as he is seen on a film from 1969—then stepping forward in pensive ronde de jambes, as if tracing a thought. It's one of the rare moments in the ballet when a character steps from the back of the stage to the front, and the variation will end with Jaegar and the Elgars—Joseph Cipolla and Silvia Jimenez—rushing forward towards us, only to turn and walk quietly, and with the utmost poetry, back to the garden arch. This phrase, too, is unusual, for most often in this ballet one is aware of the characters moving backwards by backing up, not by turning their backs on us. Nonetheless, even in the dramatic moments of frontal emphasis, here and elsewhere, there is absolutely no breaking of the fourth wall in "Enigma." Indeed I could argue, and I think I will argue, that there ought not to be any breaking of that wall in any of the Ashton I've seen this first week of the Ashton Festival, though people seem to do it, in a mistaken effort at charm, which if course is by nature effortless, and imbued in the steps.

Because much of the "Enigma" choreography is oblique, it is by its nature enigmatic. Because of the fabled Ashton use of the upper torso, characters are on a diagonal even when they do move forward. The feet move forward, the head inclines towards one side, or the other. And, just so, the movement, often, inclines first to one side, then to the other, in repeating motifs, in doubling, in inversion, in repetition. These devices allow for a visual ease in the viewing experience—you have time to absorb the phrasing, and to breathe it in along with the music. The effect of one is immersion and absorption—you are drawn into the ballet's world.

And yet, as Ashton was distant from Elgar, so are we from Ashton. Just as Ashton could see the shape of Elgar's life whole, we can see the shape of Ashton's life whole. Thus if, in viewing the" Nimrod," you are tempted to substitute Ashton for Jaegar and see the choreographer in duet with the composer, you will not have gone too far astray. You will merely be seeing the work from the present. And if you should see, in the person of Lady Elgar, the ballet itself—partnered by both Sir Edward and Sir Fred—lifted aloft by each in turn, and, in the end, gently inclining her fine head towards the choreographer to make her elegiac exit, that will be just another solution, among the many, of the enigma.

"

The Enigma Variations" was followed, last Friday, by "The Two Pigeons," a love story involving a faithless artist boyfriend who abandons his soul mate, of whom he has tired, to try his luck with the girlfriend from hell—namely, a gypsy hot tamale with an ominous boyfriend who lurks in the background, only to come forward in Act II as a kind of Benno, the third wheel in a pas de trois. In the end, the prodigal boyfriend, having been spurned by the hot number—Molly Smolen reminded me of Barbara Stanwyck in "Ball of Fire," but without the heart—and having been roughed up by her retinue, returns to his rooftop garret where his true love awaits. The key conceit here is avian; there are two actual pigeons—trained birds—that symbolize the lovers, who have, especially the girl, pigeon movement motifs. As she is dressed in white and the gypsy is dressed in black, I whiled away my over-long time in the gypsy encampment (the gypsies are to gypsies as the pirates of Penzance are to pirates) thinking about how it was possible to analyze the ballet as a version of "Swan Lake."

White swan, black swan. White pigeon, dark gypsy. This in turn reminded me of how Balanchine subsumes the classics in his repertory, so I had an interesting time. To support my "Swan Lake" premise, I offer you the evidence of the first act, when the Young Girl, who was danced by Nao Sakuma, is joined by a flock of girlfriends, and they all do pigeon dances—the Pigeon Queen and her flock; and I offer you as another swan reference the evidence of the ending, when the girl is folded on the floor in repose, her fluttering wings stilled, her torso resting on her extended legs, too Pavlova for words. This is how The Young Man, danced by the "Shropshire Lad"-ish Andy Parker, finds her, when he is inspired to return by one of the actual pigeons, who lights on his hand—or ought to, according to the Ashton expert Alastair Macaulay, though at this performance the bird had to be sought in the wings. The ending is very picturesque, with the dancers framed in the oval back of a Victorian chair frame, intertwined in a way that recalls "Fille Mal Gardée," that ultimate Ashton charmer. Just before the curtain, a second pigeon flies in to perch with the first over the heads of the lovers.

I found some details of the performance too audience oriented, but having never seen the ballet before, I was merely intuiting this. I wanted to gaze into the world of the ballet, and I didn't want it to be gazing back, or worse, soliciting my attention. Further, a ballet with a gypsy caravan is never going to be my favorite thing, but I feel I should mention that after I had learned more about the work—in specific, after Vaughan and Macaulay had explicated some of the reasons they love it, in a Saturday afternoon symposium presented in association with The New York Library for the Performing—I found I enjoyed it more myself at a second viewing. They had been eloquent about the underpinnings—the craft, the structure—and so I found myself reconciled to the adorableness of it all, and almost willing to remember, for all that I've enjoyed forgetting, what it is like to be young, in love, and betrayed.

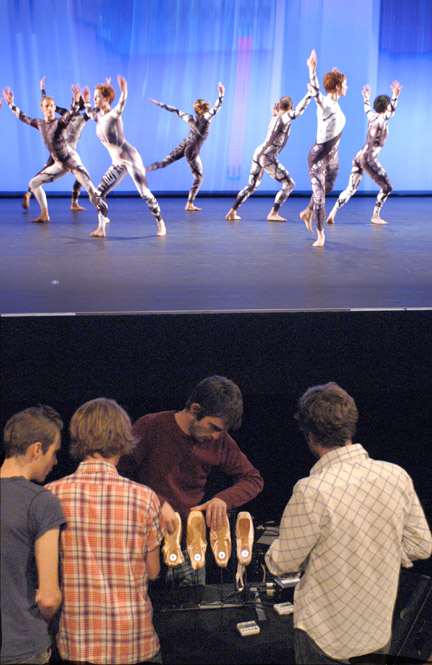

Photos, both by Stephanie Berger, taken July 7, 2004.:

First: Joseph Cipolla and Silvia Jimez of the Birmingham Royal Ballet in "Enigma Variations." Performance shot by Stephanie Berger.

Second: "The Two Pigeons."

Originally published:

July 11, 2004

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Ashton Section

Copyright ©2004, 2011 by Nancy Dalva

"The Enigma Variations" was followed, last Friday, by "The Two Pigeons," a love story involving a faithless artist boyfriend who abandons his soul mate, of whom he has tired, to try his luck with the girlfriend from hell—namely, a gypsy hot tamale with an ominous boyfriend who lurks in the background, only to come forward in Act II as a kind of Benno, the third wheel in a pas de trois. In the end, the prodigal boyfriend, having been spurned by the hot number—Molly Smolen reminded me of Barbara Stanwyck in "Ball of Fire," but without the heart—and having been roughed up by her retinue, returns to his rooftop garret where his true love awaits. The key conceit here is avian; there are two actual pigeons—trained birds—that symbolize the lovers, who have, especially the girl, pigeon movement motifs. As she is dressed in white and the gypsy is dressed in black, I whiled away my over-long time in the gypsy encampment (the gypsies are to gypsies as the pirates of Penzance are to pirates) thinking about how it was possible to analyze the ballet as a version of "Swan Lake."

"The Enigma Variations" was followed, last Friday, by "The Two Pigeons," a love story involving a faithless artist boyfriend who abandons his soul mate, of whom he has tired, to try his luck with the girlfriend from hell—namely, a gypsy hot tamale with an ominous boyfriend who lurks in the background, only to come forward in Act II as a kind of Benno, the third wheel in a pas de trois. In the end, the prodigal boyfriend, having been spurned by the hot number—Molly Smolen reminded me of Barbara Stanwyck in "Ball of Fire," but without the heart—and having been roughed up by her retinue, returns to his rooftop garret where his true love awaits. The key conceit here is avian; there are two actual pigeons—trained birds—that symbolize the lovers, who have, especially the girl, pigeon movement motifs. As she is dressed in white and the gypsy is dressed in black, I whiled away my over-long time in the gypsy encampment (the gypsies are to gypsies as the pirates of Penzance are to pirates) thinking about how it was possible to analyze the ballet as a version of "Swan Lake."

In the past year, The Merce Cunningham Dance Company has performed “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run” in, among other cities, Chicago and Washington D. C., and it is the final work on the opening night program of the Fall for Dance Festival on September 28th at City Center in New York. Dance Theatre of Harlem, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, STREB, and David Neuman will precede the company on the mixed bill. As it happens, Mr. Jones is an admirer of Mr. Cunningham’s work, as is Elizabeth Streb. She was in turn admired early on in her career by John Cage and Mr. Cunningham—who recommended her work to me in the early 1980s—so the program makes a certain amount of sense as something other than a random sampler. Besides, “How To” is the only work in the Cunningham repertory in which the choreographer himself still takes a part, and it is nice to think of him being on stage again at City Center, where his company for so many years performed every spring.

In the past year, The Merce Cunningham Dance Company has performed “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run” in, among other cities, Chicago and Washington D. C., and it is the final work on the opening night program of the Fall for Dance Festival on September 28th at City Center in New York. Dance Theatre of Harlem, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, STREB, and David Neuman will precede the company on the mixed bill. As it happens, Mr. Jones is an admirer of Mr. Cunningham’s work, as is Elizabeth Streb. She was in turn admired early on in her career by John Cage and Mr. Cunningham—who recommended her work to me in the early 1980s—so the program makes a certain amount of sense as something other than a random sampler. Besides, “How To” is the only work in the Cunningham repertory in which the choreographer himself still takes a part, and it is nice to think of him being on stage again at City Center, where his company for so many years performed every spring. At the opening of the work as it currently is presented, Mr. Cunningham is seated at a table to the far left of the stage, on the part called the “apron.” At his right is David Vaughan, in his own original role as one of the narrators of the score, which is a series of vignettes, of varying lengths, each read aloud so as to take up exactly a minute. (Thus some are spoken rapidly, some slowly, some somewhere in between. Sometimes the narrators overlap. The material was drawn by Mr. Cage from his “Stories from Silence,” published by Wesleyan University Press in 1961, and other Cage texts.) To Mr. Cunningham’s left, Mr. Swinston takes up a position, and, just before initiating the movement by emphatically torquing his body, he acknowledges the choreographer. This is not so much a visual exchange as an energy exchange; a current runs between them. It is a potent moment on its own—and was so all along, originally being between Mr. Cunningham and Mr. Cage, launching their separate parts of the work, which are synchronous but not interdependent adventures. If you know the back story, the moment is now more potent still. Continuity, change. The passage of time imposes its own narrative, singular, but universal. That Mr. Swinston is no longer in the first flush of youth—he is in fact somewhat older than Mr. Cunningham was when the work premiered—but is rather an authoritative and magisterial presence in his own right, adds resonance to the performance, and authenticity.

At the opening of the work as it currently is presented, Mr. Cunningham is seated at a table to the far left of the stage, on the part called the “apron.” At his right is David Vaughan, in his own original role as one of the narrators of the score, which is a series of vignettes, of varying lengths, each read aloud so as to take up exactly a minute. (Thus some are spoken rapidly, some slowly, some somewhere in between. Sometimes the narrators overlap. The material was drawn by Mr. Cage from his “Stories from Silence,” published by Wesleyan University Press in 1961, and other Cage texts.) To Mr. Cunningham’s left, Mr. Swinston takes up a position, and, just before initiating the movement by emphatically torquing his body, he acknowledges the choreographer. This is not so much a visual exchange as an energy exchange; a current runs between them. It is a potent moment on its own—and was so all along, originally being between Mr. Cunningham and Mr. Cage, launching their separate parts of the work, which are synchronous but not interdependent adventures. If you know the back story, the moment is now more potent still. Continuity, change. The passage of time imposes its own narrative, singular, but universal. That Mr. Swinston is no longer in the first flush of youth—he is in fact somewhat older than Mr. Cunningham was when the work premiered—but is rather an authoritative and magisterial presence in his own right, adds resonance to the performance, and authenticity.  Of all of the multiple innovations in the work of Merce Cunningham, the use of chance is the most confusing. Such a clear thing, this toss of a die, or a handful of pennies, and yet chance is the Holy Ghost of Dance—the part of the Cunningham Trinity taken on faith, and dimly apprehended. The independence of dance as an art form–the notion that dance does not need music, but may simply coexist with it—still may seem heresy to some, but as an idea it is well understood. The separation of dance from story is now old hat, or old enough, though still giving rise to the notion that Cunningham's dances are "abstract," when dance, because it is done by people, can never really be abstract. But chance! Chance makes people think of randomness, of disorder, of improvisation, of fate and fortune, of things made up as they are happening, or just before. Nothing, though, could be further from the Merceian truth, which is quite the opposite. His is not the unhinged Miltonic world of Paradise Lost, where "Chaos umpire sits," and "Chance governs all." Not in the slightest. In his world, Merce governs all, even when by a kind of non-doing, this latter being neither benign nor malign, but a kind of sovereign absenting of ego. Even when Cunningham does not make choices—as when, for instance, he leaves the decor to the art director, or some similar personage, who chooses the artists; and likewise hands off the music—he has chosen the chooser. The truth is that in his world, Cunningham is God. Every choice, or non-choice, is made by him.

Of all of the multiple innovations in the work of Merce Cunningham, the use of chance is the most confusing. Such a clear thing, this toss of a die, or a handful of pennies, and yet chance is the Holy Ghost of Dance—the part of the Cunningham Trinity taken on faith, and dimly apprehended. The independence of dance as an art form–the notion that dance does not need music, but may simply coexist with it—still may seem heresy to some, but as an idea it is well understood. The separation of dance from story is now old hat, or old enough, though still giving rise to the notion that Cunningham's dances are "abstract," when dance, because it is done by people, can never really be abstract. But chance! Chance makes people think of randomness, of disorder, of improvisation, of fate and fortune, of things made up as they are happening, or just before. Nothing, though, could be further from the Merceian truth, which is quite the opposite. His is not the unhinged Miltonic world of Paradise Lost, where "Chaos umpire sits," and "Chance governs all." Not in the slightest. In his world, Merce governs all, even when by a kind of non-doing, this latter being neither benign nor malign, but a kind of sovereign absenting of ego. Even when Cunningham does not make choices—as when, for instance, he leaves the decor to the art director, or some similar personage, who chooses the artists; and likewise hands off the music—he has chosen the chooser. The truth is that in his world, Cunningham is God. Every choice, or non-choice, is made by him. The company's general manager, Trevor Carlson, whose energizing notion it was to commission the rockers, has also arranged for two sets, both by photographers. One is by the 18-year old Robert C. Heishman, who works in black and white ( often using cameras made from everyday objects, with film in one end and a pin hole at the other.) The other is by Catherine Yass, working in color (using a large-format camera, and layering and lighting techniques to produce composite images with manipulated and heightened coloration).

The company's general manager, Trevor Carlson, whose energizing notion it was to commission the rockers, has also arranged for two sets, both by photographers. One is by the 18-year old Robert C. Heishman, who works in black and white ( often using cameras made from everyday objects, with film in one end and a pin hole at the other.) The other is by Catherine Yass, working in color (using a large-format camera, and layering and lighting techniques to produce composite images with manipulated and heightened coloration). For while the elements stayed the same from performance to performance (although I guess you could quibble about the music, which has some built-in allowance for spontaneity), they would vary in their combination, though very slightly, as chance had it. The affect of the choreography, and the effect, would change from performance to performance, depending on the order of its arrival, what it wore, and where it was. (Just as you yourself appear different in a bathing suit at the beach or a winter coat at a funeral, though you may be standing the same way, and thinking the same thing.) One could make an aesthetic judgement about the various results; one might have a preference. From evening to evening, one went home floating on air, or shuddering. The audience response was vivid each night—the houses were sold out, right up to the rafters—but the group preference was clearly for color, for pleasure, and for a happy ending. So it was on the first night, which went from dark to light.

For while the elements stayed the same from performance to performance (although I guess you could quibble about the music, which has some built-in allowance for spontaneity), they would vary in their combination, though very slightly, as chance had it. The affect of the choreography, and the effect, would change from performance to performance, depending on the order of its arrival, what it wore, and where it was. (Just as you yourself appear different in a bathing suit at the beach or a winter coat at a funeral, though you may be standing the same way, and thinking the same thing.) One could make an aesthetic judgement about the various results; one might have a preference. From evening to evening, one went home floating on air, or shuddering. The audience response was vivid each night—the houses were sold out, right up to the rafters—but the group preference was clearly for color, for pleasure, and for a happy ending. So it was on the first night, which went from dark to light. The costumes were happy and bright and sugary, the photographic backdrop smeared buildings into towering pastel after dinner mints, and Sigur Rós reached for a xylophone, a battery of timpani constructed of toe shoes, the recorded sounds of a baby cooing, and some wind-up devices they happily used to tick-tock along with what they could see from the pit. Thus as Derry Swan spun thrice around her partner Cedric Andrieux, Venus cavorting with Mars, the musicians made merry matching sounds. (For those who were appalled by this, I would only point out that the late David Tudor, Cunningham's music director after Cage's death, and a long time pit musician and composer for the company, by his own admission did the same thing, though not in such a rudimentary way. He admitted this backstage at the Paris Opera, after the first performance of Enter, when he could be seen ramping up the sound when the stage grew dark and dull and overshadowed by the set, as if in counter-balance. In other words, if there are rules, they've already been broken, albeit broken better.)

The costumes were happy and bright and sugary, the photographic backdrop smeared buildings into towering pastel after dinner mints, and Sigur Rós reached for a xylophone, a battery of timpani constructed of toe shoes, the recorded sounds of a baby cooing, and some wind-up devices they happily used to tick-tock along with what they could see from the pit. Thus as Derry Swan spun thrice around her partner Cedric Andrieux, Venus cavorting with Mars, the musicians made merry matching sounds. (For those who were appalled by this, I would only point out that the late David Tudor, Cunningham's music director after Cage's death, and a long time pit musician and composer for the company, by his own admission did the same thing, though not in such a rudimentary way. He admitted this backstage at the Paris Opera, after the first performance of Enter, when he could be seen ramping up the sound when the stage grew dark and dull and overshadowed by the set, as if in counter-balance. In other words, if there are rules, they've already been broken, albeit broken better.)  By neccessity, Split Sides looks like a Cunningham Event, one of those signature amalgams of parts of various dances, rather than one of the great repertory works possessed of an ineluctible inevitablity. Because the halves can run in either order, they have to have beginnings and ends that won't put a dancer in two places at once, or in one place wearing one costume one second, and another the next. Thus the troupe is divided in half at signal junctures. But company and continuity are not the only things split.The body itself is split every which way—one half against another, side to side, top to bottom—and dancers themselves are split, even when dancing together. As evidence there exists the most difficult, cool, clinical duet ever devised by Cunningham, danced by two virtuosi of the impossible, the firebrand Holly Farmer and the soulful Daniel Squire. In this encounter, neither seems to have anything to do with the other, and yet they intersect, with hostile inadvertence. Finally, in anything but abandonment—she gives the feeling she could just reverse course with no need of a partner—Farmer falls back into Squire's arms in just the way that Cathy Kerr fell back into Alan Good's arms in the Cunningham masterpiece Points in Space. So similar, so different.

By neccessity, Split Sides looks like a Cunningham Event, one of those signature amalgams of parts of various dances, rather than one of the great repertory works possessed of an ineluctible inevitablity. Because the halves can run in either order, they have to have beginnings and ends that won't put a dancer in two places at once, or in one place wearing one costume one second, and another the next. Thus the troupe is divided in half at signal junctures. But company and continuity are not the only things split.The body itself is split every which way—one half against another, side to side, top to bottom—and dancers themselves are split, even when dancing together. As evidence there exists the most difficult, cool, clinical duet ever devised by Cunningham, danced by two virtuosi of the impossible, the firebrand Holly Farmer and the soulful Daniel Squire. In this encounter, neither seems to have anything to do with the other, and yet they intersect, with hostile inadvertence. Finally, in anything but abandonment—she gives the feeling she could just reverse course with no need of a partner—Farmer falls back into Squire's arms in just the way that Cathy Kerr fell back into Alan Good's arms in the Cunningham masterpiece Points in Space. So similar, so different. Same old, same old, one should think. But no. The consequent change to the work is astonishing. Brought forth by a few rolls of a single die, tragedy comes calling. The first part, all warmth and sweetness, with young Jonah in his solo and the four couples in their love song, yields to the harsh wintry second part, with the dancers looking like extremely intelligent aliens who have just this moment come to inhabit human bodies, trying them out for the first time without knowing any of the human rules of moving. The eye glances off what it does not recognize—the glinting surface of the unfamiliar, as glances, too, the mind. Bleak, bleak, bleak—the summer of the first half giving way to winter, sunlit youth yielding to starlit age, remote and chill.

Same old, same old, one should think. But no. The consequent change to the work is astonishing. Brought forth by a few rolls of a single die, tragedy comes calling. The first part, all warmth and sweetness, with young Jonah in his solo and the four couples in their love song, yields to the harsh wintry second part, with the dancers looking like extremely intelligent aliens who have just this moment come to inhabit human bodies, trying them out for the first time without knowing any of the human rules of moving. The eye glances off what it does not recognize—the glinting surface of the unfamiliar, as glances, too, the mind. Bleak, bleak, bleak—the summer of the first half giving way to winter, sunlit youth yielding to starlit age, remote and chill.